The Sourcing Artistry of WRJ Design

In storytelling, the tale begins when the main character walks out the front door. However, it is the philosophy of Rush Jenkins, CEO of WRJ Design, in Jackson Hole, that the story must always begin when you walk in the door.

“For us, design has never been about just fabrics and furniture,” explains Jenkins. “A chair is a chair. Real design is about sourcing the many layers of history, culture, craftsmanship and nature. We’re far more interested in bringing depth and context to the project—and creating real emotion—because that’s who we are, and we seek out a clientele who will appreciate this.”

The layers Jenkins alludes to can be found in his partner’s, Klaus Baer’s, Austrian heritage and experience managing international investment production teams, and in their Director of Design Nida Zgjani’s upbringing in Albania, where she studied architecture at the University of Engineering. It is also evident in Jenkins’ own rich history working with Sotheby’s in London and New York.

Additionally, Jenkins continues to thrill as the creator of exhibits; most recently, he received accolades for his show at the St. Petersburg Museum of Fine Arts featuring the one-of-a-kind jewelry of Jean Schlumberger.

“We are more than designers,” adds Baer. “We are curators, collectors and stewards, passing on our passion to our clients. WRJ is about the discovery of wonderful things. This discovery happens for us in Paris and in the auction houses of New York. It happens on Portobello Road and in the streets of London and in the bazaars of Turkey. We’re looking to tell a story, to create real magic, because when that happens, suddenly the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts.”

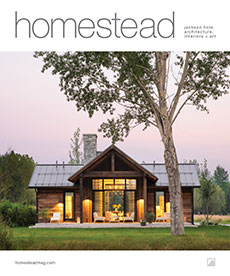

In this particular home, a collaboration with the clients and JLF Architects, the stories are everywhere.

“I’d be in a meeting,” recounts the owner about the early design stages of her home, “and I’d get this text from Rush in Paris, saying, ‘You have to see this!’ I’d excuse myself to look at a photograph of a set of tables or a lamp with this blue-green labradorite stone mounted on it. I came to trust him because he always seemed to know. And it was so much fun.”

The motto of WRJ Design is: “Inspired by the natural world. Informed by the rest of it,” which is why they’ve always worked so well with JLF, architectural visionaries who’ve also established a reputation for seeking new ways to bring the outside in and nestle their structures within their surroundings.

“The beauty of working with Rush and Klaus,” explains JLF design principal Paul Bertelli, “is that when we start the planning process with them, they get it. The goal posts are clearly defined and we’re all working toward that same uniqueness. They get that our buildings are integrated. They’re one piece. The inside informs the outside and vice versa. A stone wall outside may very well run through the entire house, so those textures and finishes have to be considered. They anticipate this, and it’s magic when it happens.”

The natural world is very much alive in this home, from the living room’s faux bois firewood bin and Van der Straeten handwrought bronze tumbleweed mirror over the fireplace to the porcupine-quill box from Ceylon in the hallway outside the master suite.

“From the beginning,” explains Zgjani, “we were after an almost zen-like harmony with plenty of light. Take the living room, for instance. We created a floor plan for how the family would interact with the space, whether during a cocktail party or an intimate family game of cards. The owners wanted a real livability, a flexibility, which would allow them to rearrange the pieces. And once we had that, we worked on our textures and tones. The Loro Piana fabrics, the Holly Hunt black-lacquered tables, which threw light everywhere, the blue-green mohair upholstery with its rich, cozy sheen, and the petrified-wooden end tables Rush found in Paris. Then we brought it all together with the custom silk-and-woolen rug from Mansour, with all those soft, neutral textures and tones found in the fabrics and stonework.”

But even within these boundaries, there was room for both whimsy and surprise. Downstairs in the hallway, for instance, there is a collection of mock historical photographs of Indians downing a fighter plane with bows and arrows. And in one of the daughters’ bedrooms, there are wonderful pink beads sewn into the white linen of the canopy.

And then there is the Syrian chest of drawers. It stands at the top of the stairs in the hallway outside the master bedroom in finely crafted dark walnut, intricately inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Topped with white Mediterranean marble, it was created sometime between 1900 and 1960 on the plains of Hauran, between Damascus and Jordan. Originally, pieces like these were crafted as bridal gifts, but they soon found a more lucrative market in the West. The mystery of how these craftsmen came by their skills in a country where only 2 percent of their land is forested is difficult to solve. With Syria at war, the artisans have either fled to Lebanon or been lost in the strife.

“Rush, Klaus and Nida knew,” says the homeowner. “From the very beginning they drilled down to an understanding of what would make our house special. And then they went out and found all these eclectic furnishings and made them work together, rich with history and story, and never contrived. We wanted a home that would feel like we’d lived there forever, and that’s what they delivered.”