Katy Niner

Photos By

Bruce Damonte + Roger Wade +

Paul Warchol

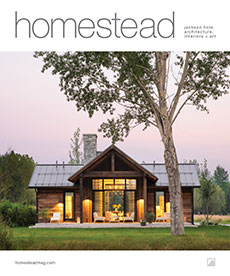

A series of female patrons has defined modern architecture in Jackson Hole as a spirited solution to the challenges of Teton properties. Over the past 80-plus years, their timely patronage of visionaries has ushered a modern infusion in Jackson.

In the 1930s, Helen Resor recruited German architect Mies van der Rohe to create a summer house on her property at the foot of the Tetons. Responding to the rugged surrounds, he designed a conceptual and physical bridge between the site and his structure by perching the living space on cement pylons above a stream and sheathing the pavilion in floor-to-ceiling glazing bold moves at the time which made for complete visual immersion in the landscape. Redefining the relationship between architecture and nature, the modernist pioneer established a new vernacular in the valley by offering a contemporary silhouette as a quiet complement to the spectacular. In his lexicon and legacy, the Snake River site dictated early modern, clean lines à la his Bauhaus background.

You are impressed with how the mountain range meets the valley floor in a very abrupt landing that creates a horizontal emphasis.

~ stephen dynia

Although the building never came to full fruition, van der Rohe’s concept remains an inspiration to valley architects, particularly in the case of two seminal structures. Like Resor, Sophie Craighead enlisted a new-to-Jackson architect, Stephen Dynia, to design her Kelly home; Doyen McIntosh recruited Casper Mork-Ulnes to realize her residence on West Gros Ventre Butte. In both instances, Craighead and McIntosh extended their connection to place into empowerment of their architects, allowing them to deploy their talents to most effectively respond to the strictures of the sites. Both homes thus honored the landscape itself through responsive structural solutions that proved to be vanguards for Jackson Hole.

Uncompromised views

The Kelly property drew Craighead and her husband, Derek, from Missoula, Montana, to Jackson in 1996. Set on the hill above town, the spectacular site contained a traditional post-and-beam home, which they initially intended as a summer house. They spent a year in it before deciding to remodel. Having worked on an office project with Dynia, a simpatico former New Yorker, Craighead sought his expertise. Her East Coast roots translated into a traditional English countryside style, whereas Dynia had a distinctly modern aesthetic, having worked at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in Manhattan. “I had never done anything modern,” Craighead says. And Dynia had yet to do a significant residence in Jackson.

The couple decided that the property deserved a responsive, dramatic design. “Not just any structure would fit this lot,” Craighead says. “It’s a powerful spot and it deserves a strong, powerful house.”

Before committing to a new construction, the Craigheads traveled to their rustic house on a remote island in the Caribbean. Completely open to nature, the house makes no delineation between outdoors and indoors. They realized they wanted the same in Jackson. “No line, no separation: We wanted the outside inside,” Craighead says. They returned from that trip and set Dynia loose to design in situ. “We pretty much gave him carte blanche,” she says. “We told him: ‘We think you are talented. Take it from here.’”

Channeling the natural eloquence of van der Rohe, Dynia distilled the primary characteristics of the site into a structural schema: Elevated above the valley, facing the Tetons, the property encompassed the alpine drama. “You are impressed with how the mountain range meets the valley floor in a very abrupt landing that creates a horizontal emphasis,” Dynia says. That horizontality—“that desire for the building to somehow parallel the mountain range”—drove the organization of the house into a grid, with each space existing as “its own lens on that view.”

The grid grew from a series of 16-foot bays, each framed by a concrete slab and column. Because the walls do not extend to the perimeter of the house and the rooms are only separated by pivoting or sliding doors, the windows and ceiling are continuous, which means “getting the most out of the view from every room,” Dynia says. This dynamic simultaneously achieves an intimacy throughout the open layout. The grid also achieves a gravitas which he traces back to the grounded ethos of traditional log homes.

To this day, Dynia sees the Craighead home as his crowning achievement. “The house was trying to be stable and heroic by that grid,” Dynia says. “I still consider it, within the context of my work over the last 20-plus years, as the most important house because of its integrity. The structure is evident, and the way it exists in the landscape is effective. I don’t know if I have done another project with as much integrity—and it has to come back to Sophie herself.”

Steep integration

McIntosh had experienced firsthand the connection to place fostered by a log house, having decamped from California to live in a Crescent H log cabin. In 2007, she decided to live out her interest in contemporary architecture, so started scouting properties with realtor Mercedes Huff. After much searching, she found a parcel perched on a 30-degree slope overlooking the Walton Ranch. Before contacting an architect, she spent time getting to know the site, unfolding a chair in different spots. Enraptured by the panorama, she set out to honor the site with a house integrated into its surrounds.

McIntosh knew Mork-Ulnes as the son-in-law of her oldest friend. A bit wary of segueing personal into professional, she was impressed by his international portfolio spanning San Francisco and Oslo—work reminiscent of Renzo Piano. In his initial presentation, Mork-Ulnes referenced Mies van der Rohe’s Resor house as a benchmark by which he would measure his modern contribution, particularly in terms of the relationship van der Rohe forged between the stream and the structure. McIntosh was sold.

Thus inspired, Mork-Ulnes embraced the rugged lot, exploring every inch before selecting a building site. Instead of imagining a bulldozed pad at the hilltop, he chose to nestle the house into the slope, an orientation that “maintained the quality of the site,” Mork-Ulnes says.

Mork-Ulnes’ low-slung design follows the natural contours of the landscape, a continuous volume that kinks at the corner to honor the profile—a key moment suggested by McIntosh’s son, Montgomery, a landscape architect who also added several native pocket gardens within the house’s skinny silhouette. Even the roofline follows the slope, titling with the angle, rather than away from it, which “helps compress the view a bit by creating a horizon line and framing the sky,” Mork-Ulnes says. Beyond aesthetic alignment, the parallel pitch provides natural lighting and ventilation: A row of clerestory windows facing uphill funnels in morning sun and allows the climbing breeze to course through the house.

Mork-Ulnes achieved simplicity amid the complications—as is his way, as was McIntosh’s desire. Eschewing a signature style, he follows a signature approach: By embracing and responding to each project’s challenges, he comes up with unique, often surprisingly simple solutions. “We let the challenges surrounding the project inform the architecture,” he says. “We let the challenges be the solution.”

This charge to integrate architecture into nature proved foundational for the young architect. Arising during his early-career throes of commercial projects, the McIntosh home served as his first foray into rural, residential design. “It was a predecessor for a lot of the work we are doing now.” As an avid outdoorsman, he says, “I’ve always had a keen interest in touching the earth lightly. Working in Jackson Hole was a dream commission.”

Six years since its completion, McIntosh remains enamored with her home. As she had hoped, the house exists in harmony with its habitat. “It’s part of the property,” she says. “It’s not obtrusive. It lets the outdoors in.” She describes it as a “seasonally changing painting,” cued by light and nature. “I’m just so enthralled with the view.”

Natural connection

Craighead and McIntosh both empowered their architects at pivotal points in their careers. The McIntosh commission came only a year after Mork-Ulnes had founded his own firm. “Doyen was a pretty amazing client in terms of the trust that she put in me at a relatively young age,” he says. “She had thought a great deal about this house, but she wasn’t prescriptive in any way. Even though we had challenges to deal with, she gave us a lot of creative freedom in terms of how to resolve the whole house. It was a fantastic experience working with her.” A glowing review mirrored by McIntosh.

For Dynia, the Craighead residence proved seminal as well, providing him with an opportunity to manifest an integrity of place and person. “The challenge and fascination of having the confidence of the owners allows for that kind of emotional response to the site,” he says. “I let the right solutions emerge from the schematic design, the right balance of strength and subordination to the site, a nuanced balance between the power of the house and the power of the landscape.”

Dynia equates the character of the house to Craighead’s character. “It’s determined and powerful, thoughtful and considerate,” he says. “It’s a commentary on the nature of the person.” House and human both ameliorate the experience of environment. “Sophie has been so effective in understanding the values of the community and helping it,” Dynia says.

Both projects testify to the integrity of place attainable when clients of integrity are involved. “If there is commonality, understanding and mutual respect, the product speaks to that condition,” Dynia says. The homes endure as homages to their rare settings and their visionary occupants.