> Story by Katy Niner

> Photography by Latham Jenkins

Distillation: Eliot Goss, “Logjam”

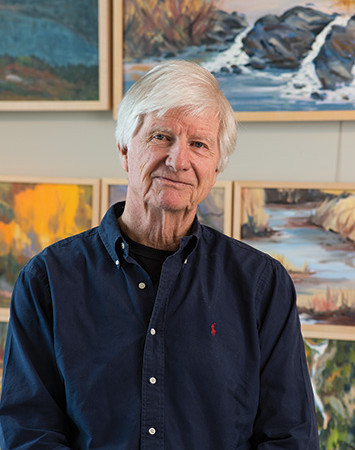

For most of his life, Eliot Goss has pursued two parallel tracks: architecture and painting. Educated on the East Coast (at Princeton and MIT), he moved west, landing first in Denver, then settling in 1990 at the foot of the Tetons. With architecture taking up 98 percent of his time, he carved out 2 percent for painting. Now, the ratio has flipped: He spends the majority of his time making art, reserving a small part for longstanding architecture clients. No longer as driven to sell his work, instead he is “trying to make as terrific a painting as I can.”

“Logjam” evolved over six months and three canvases. Last summer, Goss spotted this tangle above the String Lake outlet, a composition made compelling by the slab boulder, the rushing water, and the deadfall pile-up. He painted a 16-by-20-inch canvas en plein air and let it sit for several months. Come winter, he zoomed in on the log angles and dark flow. By the following spring, he moved up in size, creating the final composition. “I take what I learn from focusing down into the painting and then going large.”

Goss works with a painting advisor, his old friend Joanna Reinhoff in Colorado. An abstract artist early in life, Reinhoff now works in poetry, with an incisive eye she applies to his paintings, approving only a small fraction. Her main advice: Focus. Eschewing the Renaissance ideal of foreground, middle ground, and background, she tells him to zero in on the most compelling idea; disregard the deep space and bring everything to the surface. Goss reconsidered past paintings, magnifying small moments of success into new works. Thirty-four studies surfaced from this exercise, including “Logjam.” He said, “You get an entirely different painting. You abstract it naturally through the process of painting. … It’s changed the way I paint and changed the way I look at landscape.”

Goss paints in two-hour stints—bursts of creativity that suit his “impatient” artistic temperament. Larger compositions begin with an underpainting, often done in purple. Over this, he adds two or three layers. This was not the case, however, with “Logjam”: It worked, miraculously, with only one layer of overpaint.

Goss initially worked in watercolors, but switched to oils 15 years ago. Recently, he began applying a plethora of mediums to portraits, attending the weekly model sessions at the Art Association. His favorites—faces in charcoal and watercolor—line the foyer of his studio; the rest he returns to the models. After so much experimentation, he appreciates the tactile nature of oils.

Magnification: Bronwyn Minton

Bronwyn Minton does not abide by classifications of genre; instead, she adventures across disciplines, merging mediums and creating processes all her own. Her latest work, part of a group ceramics show at the Center for the Arts, blends drawing, photography, sculpture, and interactive installation. Creative in all avenues of her life, Minton spends her days working as the associate curator of art and research at the National Museum of Wildlife Art; nights and weekends find her experimenting in her home studio, playing with her son, Odin, or cooking with her husband, Mike.

Minton is fascinated with lenses: mythological, literary, and scientific. Although she studied photography at the Rhode Island School of Design, she has since stepped away from the camera. And yet, the act of looking remains crucial to her practice. Metaphoric in her mind, lenses frame a view, whether magnified or distorted.

magnified by the lenses.

The installation’s design emulates the way Minton draws—the doodles she makes, the intuitive marks

on paper, the evidence of hand-to-eye communication. Equipped with components cast in her studio, she

composes her installations on-site.

Growing up with creative parents in bucolic Vermont, Minton’s childhood brimmed with experimenting and making. “I was always encouraged to try things and work with different ideas and media.” She carried this intrepid sense of inquiry with her into the problem-solving art program at RISD.

Minton builds large installations out of small pieces, akin to individuals making up a community or granules forming a beach—all models of magnification. She sees patterns: the play of tiny things, of light on water, of cells in organisms. “I use simple forms derived from nature as a starting point, often exploiting radically different scale, from the microscopic to the monumental.”

Through reoccurring experiments, Minton explores the interface between humans and nature. “I am fascinated by how mythology, literature, and science form lenses through which we have interactions with nature.” On hikes, whether around town or on vacation, Minton collects objects found in nature: seed pods, shed shells, botanical tufts. Her sculpted “specimens” grow from these ground finds, as she plays with scale, making the microscopic monumental, and through simplification, distilling detail into essence.

Look-See: Mike Piggott, “Another Place”

Wander into Mike Piggott’s world and stay awhile. There are no rules for interpretation; see whatever you see. Let yourself experience the art, as he always has: Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, schooled at Virginia Commonwealth University and the Winchester College of Art in England, Piggot now knows the mountains and forests of Jackson Hole.

Piggott observes art as he does nature: ever open to learning. At a recent exhibition of David Hockney’s new work at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, he felt awestruck by the artist’s refreshingly close gaze: One room featured the same stretch of road near Hockney’s Yorkshire home, reconsidered in all four seasons. Piggott felt inspired by how much fun the septuagenarian seemed to be having, pulling big canvases from his trunk and painting en plein air with the enthusiasm of a teenager. “Hockney is someone who actually looks at something,” he said. “He is painting about the process of painting and looking.”

Some paintings are all-consuming and cerebral, where Piggott finds himself engrossed for a weekend. Others grow at their own pace, like “Another Place.”

A colorist, Piggott lets his paintbrush wander with associations. “Another Place” began with the log stump, which reminded him of Tootsie Rolls. The looping lasso

arrived soon after, the perfect perch for birds. The butter-colored fog seemed to ground the composition. Ever inventorying the imagery, Piggott describes this process as following his nose. He trusts his instinct to “toss an F sharp in there.”

Piggott paints from looking. “In the process of painting or drawing, you learn about what you are looking at.” While other works in his portfolio give clues to his surroundings, “Another Place” pulls from a place of automatic, almost formalist instinct. Like a collage, it accumulated elements over three years, with parts borrowed or morphed from other canvases. An orange paint mixed for another piece made him think of candy corn, and placing the cones close to birds felt right: Spotting a bird on a walk through the woods is, for him, much like being a kid in a candy shop.

Wild One: Amy Ringholz, “Living Proof”

Ohio born and bred, Amy Ringholz once spent a semester in the mountains of New Mexico and resolved to be as bold as nature in her painting. With her art diploma in hand, she drove west to Wyoming to explore the wildness she imagined. Flash forward 10 years and Ringholz had become a Teton trailblazer as the youngest artist ever featured by the Jackson Hole Fall Arts Festival. Never one to rest on her laurels, Ringholz parlayed her Fall Arts triumph into a new career trajectory: A year ago, she pulled her paintings from most galleries and established Ringholz Studios with the goal of immersing art lovers in inspiration. Through events she produces and scholarships she funds via sales,

Ringholz shares her wild muse with the rest of the world.

The phoenix is the spirit animal of Ringholz Studios, specifically its Middle English variant, Fenix, and all its mythology. Fenixes are female; only one exists at a time; their life cycles are ash-born and blazing. Since launching Ringholz Studios, Ringholz has hosted a series of Fenixes, each event larger in magical scale. Last summer at the National Museum of Wildlife Art, she staged the “Rise of the Fenix” event and exhibition. “Living Proof” was the first piece she painted for her modern menagerie. Measuring 72 by 72 inches, it remains one of the largest canvases she has ever completed.

Keen to combine fashion and wildlife art, Ringholz imagined her animals as models on a runway. For inspiration, she turned to the pages of Vogue, studying the palettes used in the spreads. Those hues informed the circular forms that set the mood, or attitude, of “Living Proof.”

Another difference at birth: “Living Proof” began with a dark background as a stage for contrast. Quite the opposite: It swallowed the geometric design. Ringholz had to wait days for the painting to dry before she could return with white. Deliberately imperfect, she wanted hints of color to peek through.

Strong and daring. Loose and free. “Living Proof” now hangs at Ringholz Studios, the brand-new gallery manifestation of Ringholz’s vision. In its new habitat, surrounded by modern décor, the deer sings.